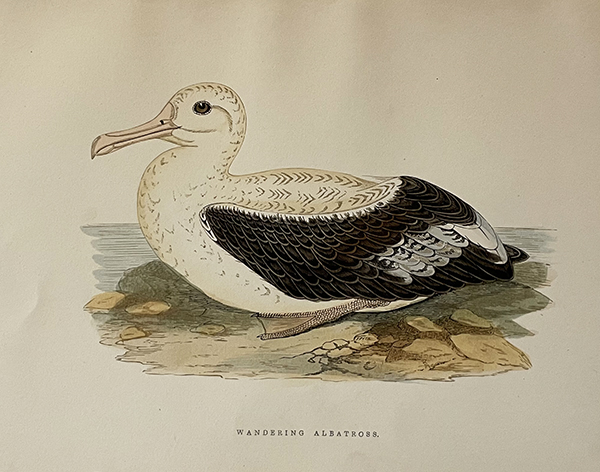

From Bree's A History of the Birds of Europe not Observed in the British Isles, 1859–63.

This last storm has brought a number of casualties here, the raging seas dumping “wrecks” of sea birds on the beaches together with logs and debris from the flooded rivers. The local bird rescuers have been very busy as people bring in birds they have found along the shores, something which has given me the opportunity to observe at close quarters three of the great birds of the Southern Ocean, a wandering albatross, Diomedea exulans, a shy mollymawk, Diomedea cauta, and a giant petrel, Macronectes halli.

Sitting around gathering strength and waiting to be fed, they seem quite content and unperturbed by our presence. They are not injured in any way, just exhausted from struggling with the extreme weather conditions. They will need some help to get up and underway again, back into their natural element, flying about the great Southern Ocean.

Most ornithologists divide the albatrosses into three groups. The first group contains the largest of all flying birds, Toroa, the wandering and royal albatrosses, which are of about equal size and easily recognised by their white backs and tails. It is to this group for which the term “albatross”, as generally understood, is reserved.

The word albatross is supposedly an English corruption of the Portuguese word ‘alcatraz’ meaning large seabird.

The second group includes those albatrosses generally referred to as mollymawks. They are smaller than the great albatrosses and easily distinguished from them by the dark back, wings and tails and usually more colourful bill. The sooty albatrosses make up the third group and are smaller again.

The shy is the largest of the mollymawks and is so named for it was seldom seen following ships. The origin of the word mollymawk is obscure but may be derived from mallemuk, the Dutch or Danish word for “stupid gull” which probably arises their lack of proper fear of humans and by their clumsiness as they walk.

Everyone comments on just how awesome and beautiful is the flight of the albatross but to see them grounded is an equally marvellous experience for they have the most remarkable eyes. The eyes of the shy mollymawk are especially beautiful, so large, gentle and intelligent and hooded by a wash of what is best described as dark mascara. All the albatrosses are credited with powerful eyesight needed to find food tossing and turning on a rough sea. One wonders if their wonderful eyes may have led to some of the superstition about them for the eyes seem almost human.

The other characteristic of these birds which can readily been seen close up is the prominent tubed nostrils. In its long flights around the Southern Ocean, very often not being near land for days and even weeks, the bird requires freshwater so it distils its own and discharges the excess salt from its system through its nostrils.

Albatrosses are among the most long–lived of birds and commonly reach the age of 30–40 years, with a record going to a Royal from the colony at Taiaroa Head near Dunedin, a bird named Grandma who was still producing young past her sixtieth birthday. The albatross is also characterised by its relative tameness, not fearing the approach of humans as most birds do.

Albatrosses are famous for their expressive courtship and affection for their mates. The courtship involves dancing and in some species such as the sooty albatross, daring chases in flight with the following bird repeating every move of the leader. The dances vary between species and are generally made up of actions used in other contexts but which appear to be adapted to the nuptial dance. These dances often have a set series of actions and reactions or responses by the courted partner. All albatrosses and mollymawks perform a form of yappering or croaking, particularly when at a nest site. They all preen their display partner or potential breeding partner, include a form of snap in their repertoire, and move their head and bill as if to preen the body feathers by the wing. The “sky call” performed with wing held out appears to be restricted to the larger albatross species. The complex interactive courtship behaviour resulting in a form of dialogue developing between displaying wandering albatrosses is typical among albatrosses. It seems likely that the complex courtship displays may allow birds, particularly females, which initiate and terminate most displays, to assess and re–assess the quality or compatibility of a potential partners before beginning the process of pair bond formation.

Using the wind, albatrosses can achieve continuous flight without beating their wings. This is known as dynamic soaring. The pattern begins with a dive with the wind behind, a swoop low over the waves and a turn and climb into the wind to attain original height. Dynamic soaring works best in what is called a “good blow”. Albatrosses are able to maintain course in a moderate wind but make leeway when wind speeds exceeds 70kmp.

The sailing ships used to encounter albatrosses while plying the westerly winds between latitudes 40 and 60 degrees, thus the Roaring Forties and the Furious Fifties came to be known as the albatross latitudes. At times they were hooked on fishing lines or shot with a cross bow or guns. One of James Cook’s expeditions records the capture of albatrosses which ended up on the table. Ashore sealers and whalers evidently took eggs and even the birds themselves for food. The use of the skins for feather rugs may have produced an early nickname “cape sheep”. Their webbed feet were converted into tobacco pouches, their bones into pipe stems, breast feathers into muffs and their beaks into paper clips.

The flesh was considered a great delicacy to Maori who preserved it the same way as mutton birds. From the bones they carved spear tips, nose flutes and other artifacts. The secretions from the birds tubular nostrils were the “tears” of the albatross, weeping for its distant home, a motif often used in carving.

The albatross feeds mostly on squid, octopus, salps and fish, a proportion of which is carrion. This scavenging behaviour in the wake of fishing vessels is leading them to becoming a threatened species. It has been calculated that 44,000 albatrosses die each year in the course of taking bait from long lines sometimes set by fishing vessels as long as 100 kilometres. The fishing companies operating in southern waters are being asked by Australia and New Zealand fisheries agencies to adopt techniques that will limit the horrendous by–catch but still the slaughter continues. It is discouraging to think that these two birds which people have gone to so much trouble to save may be drowned on a long line once they have been released.

When the time comes to return these great birds to their proper element, the local Department of Conservation officers will either have to take them out to sea or to some a cliff where they can be encouraged to take off. To take off from the sea the albatross runs on its huge webbed feet until it gains sufficient momentum to lift off. On land it will need some sloping ground on a cliff where it can, facing the wind and running to gain impetus, rise into the air.

Waiotahi Valley, Opotiki, 1999.

From Gould's Birds of Australia, 1840–48.

From Godman's Monograph of the Petrels, 1907-1910.

From Edwards' Natural History of Uncommon Birds, and some other Rare and undescribed animals, Quadrupeds, Reptiles, Fishes, Insects, 1743–1751.

From Buller's Birds of Mew Zealand, 1888.

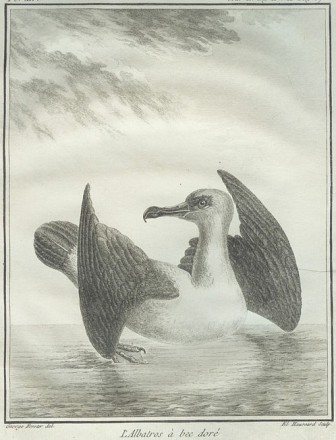

Forster, George, unknown publication.

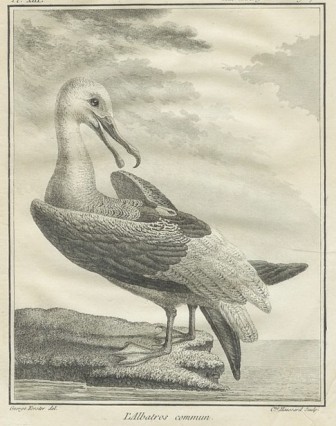

Forster, George, unknown publication.

| Taxonomy | |

|---|---|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Procellariiformes |

| Family: | Diomedeidae |

| Genera: | Diomedea |

| Species: | exulans |

| Sub Species: | antipodensis, gibsoni, chionoptera |

Wanderer, snowy albatross, Goonie birds, Gooney birds.

Native bird

115 cm., 6.5 kg., variable plumage according to age and race; upper wings black to blackish, all have a huge bill light pink with creamy tip and no black on cutting edges, underwing white but with edge and tips black, tail usually black tipped, legs and feet pinkish to browny grey.

In the New Zealand region, breeding in the Antipodes, Auckland and Campbell Islands. Seen mainly in winter off the coast, especially around Stewart Island and Cook Strait.

Bree, Charles Robert, A History of the Birds of Europe not Observed in the British Isles, 1859–63.

Gould, John, Birds of Australia, 1840–48.

Godman, Frederick du Cane, Monograph of the Petrels, 1907-1910.

Edwards, George, Natural History of Uncommon Birds, and some other Rare and undescribed animals, Quadrupeds, Reptiles, Fishes, Insects, 1743–1751.

Buller, Walter Lawry, Birds of Mew Zealand, 1888.

Forster, George, unknown publication.

Oliver, W.R.B. New Zealand Birds, 1955.

Poetry: —

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

It is an ancient Mariner,

And he stoppeth one of three.

“By thy long grey beard and glittering eye,

Now wherefore stopp’st thou me?

“The Bridegroom’s doors are opened wide,

And I am next of kin;

The guests are met, the feast is set:

May’st hear the merry din.”

He holds him with his skinny hand,

“There was a ship,” quoth he.

“Hold off! unhand me, grey–beard loon!”

Eftsoons his hand dropt he.

He holds him with his glittering eye —

The Wedding–Guest stood still,

And listens like a three years child:

The Mariner hath his will.

The Wedding–Guest sat on a stone:

He cannot chuse but hear;

And thus spake on that ancient man,

The bright–eyed Mariner.

The ship was cheered, the harbour cleared,

Merrily did we drop

Below the kirk, below the hill,

Below the light–house top.

The Sun came up upon the left,

Out of the sea came he!

And he shone bright, and on the right

Went down into the sea.

Higher and higher every day,

Till over the mast at noon-

The Wedding–Guest here beat his breast,

For he heard the loud bassoon.

The bride hath paced into the hall,

Red as a rose is she;

Nodding their heads before her goes

The merry minstrelsy.

The Wedding–Guest he beat his breast,

Yet he cannot chuse but hear;

And thus spake on that ancient man,

The bright–eyed Mariner.

And now the storm–blast came, and he

Was tyrannous and strong:

He struck with his o’ertaking wings,

And chased south along.

With sloping masts and dipping prow,

As who pursued with yell and blow

Still treads the shadow of his foe

And forward bends his head,

The ship drove fast, loud roared the blast,

And southward aye we fled.

And now there came both mist and snow,

And it grew wondrous cold:

And ice, mast–high, came floating by,

As green as emerald.

And through the drifts the snowy clifts

Did send a dismal sheen:

Nor shapes of men nor beasts we ken–

The ice was all between.

The ice was here, the ice was there,

The ice was all around:

It cracked and growled, and roared and howled,

Like noises in a swound!

At length did cross an Albatross:

Thorough the fog it came;

As if it had been a Christian soul,

We hailed it in God–s name.

It ate the food it ne–er had eat,

And round and round it flew.

The ice did split with a thunder–fit;

The helmsman steered us through!

And a good south wind sprung up behind;

The Albatross did follow,

And every day, for food or play,

Came to the mariners– hollo!

In mist or cloud, on mast or shroud,

It perched for vespers nine;

Whiles all the night, through fog–smoke white,

Glimmered the white Moon–shine.

“God save thee, ancient Mariner!

From the fiends, that plague thee thus!–

Why look’st thou so?” — With my cross–bow

I shot the albatross.

THE Sun now rose upon the right:

Out of the sea came he,

Still hid in mist, and on the left

Went down into the sea.

And the good south wind still blew behind

But no sweet bird did follow,

Nor any day for food or play

Came to the mariners’ hollo!

And I had done an hellish thing,

And it would work ’em woe:

For all averred, I had killed the bird

That made the breeze to blow.

Ah wretch! said they, the bird to slay

That made the breeze to blow!

Nor dim nor red, like God’s own head,

The glorious Sun uprist:

Then all averred, I had killed the bird

That brought the fog and mist.

’Twas right, said they, such birds to slay,

That bring the fog and mist.

The fair breeze blew, the white foam flew,

The furrow followed free:

We were the first that ever burst

Into that silent sea.

Down dropt the breeze, the sails dropt down,

’Twas sad as sad could be;

And we did speak only to break

The silence of the sea!

All in a hot and copper sky,

The bloody Sun, at noon,

Right up above the mast did stand,

No bigger than the Moon.

Day after day, day after day,

We stuck, nor breath nor motion;

As idle as a painted ship

Upon a painted ocean.

Water, water, every where,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, every where,

Nor any drop to drink.

The very deep did rot: O Christ!

That ever this should be!

Yea, slimy things did crawl with legs

Upon the slimy sea.

About, about, in reel and rout

The death–fires danced at night;

The water, like a witch’s oils,

Burnt green, and blue and white.

And some in dreams assured were

Of the spirit that plagued us so:

Nine fathom deep he had followed us

From the land of mist and snow.

And every tongue, through utter drought,

Was withered at the root;

We could not speak, no more than if

We had been choked with soot.

Ah! well a-day! what evil looks

Had I from old and young!

Instead of the cross, the Albatross

About my neck was hung.

“I fear thee, ancient Mariner!

I fear thy skinny hand!

And thou art long, and lank, and brown,

As is the ribbed sea–sand.

“I fear thee and thy glittering eye,

And thy skinny hand, so brown.”–

Fear not, fear not, thou Wedding–Guest!

This body dropt not down.

Alone, alone, all, all alone,

Alone on a wide wide sea!

And never a saint took pity on

My soul in agony.

The many men, so beautiful!

And they all dead did lie:

And a thousand thousand slimy things

Lived on; and so did I.

I looked upon the rotting sea,

And drew my eyes away;

I looked upon the rotting deck,

And there the dead men lay.

I looked to Heaven, and tried to pray:

But or ever a prayer had gusht,

A wicked whisper came, and made

my heart as dry as dust.

I closed my lids, and kept them close,

And the balls like pulses beat;

For the sky and the sea, and the sea and the sky

Lay like a load on my weary eye,

And the dead were at my feet.

The cold sweat melted from their limbs,

Nor rot nor reek did they:

The look with which they looked on me

Had never passed away.

An orphan’s curse would drag to Hell

A spirit from on high;

But oh! more horrible than that

Is a curse in a dead man’s eye!

Seven days, seven nights, I saw that curse,

And yet I could not die.

The moving Moon went up the sky,

And no where did abide:

Softly she was going up,

And a star or two beside.

Her beams bemocked the sultry main,

Like April hoar–frost spread;

But where the ship’s huge shadow lay,

The charmed water burnt alway

A still and awful red.

Beyond the shadow of the ship,

I watched the water–snakes:

They moved in tracks of shining white,

And when they reared, the elfish light

Fell off in hoary flakes.

Within the shadow of the ship

I watched their rich attire:

Blue, glossy green, and velvet black,

They coiled and swam; and every track

Was a flash of golden fire.

O happy living things! no tongue

Their beauty might declare:

A spring of love gushed from my heart,

And I blessed them unaware:

Sure my kind saint took pity on me,

And I blessed them unaware.

The self same moment I could pray;

And from my neck so free

The Albatross fell off, and sank

Like lead into the sea.

OH sleep! it is a gentle thing, Beloved from pole to pole!

To Mary Queen the praise be given!

She sent the gentle sleep from Heaven,

That slid into my soul.

The silly buckets on the deck,

That had so long remained,

I dreamt that they were filled with dew;

And when I awoke, it rained.

My lips were wet, my throat was cold,

My garments all were dank;

Sure I had drunken in my dreams,

And still my body drank.

I moved, and could not feel my limbs:

I was so light — almost

I thought that I had died in sleep,

And was a blessed ghost.

And soon I heard a roaring wind:

It did not come anear;

But with its sound it shook the sails,

That were so thin and sere.

The upper air burst into life!

And a hundred fire–flags sheen,

To and fro they were hurried about!

And to and fro, and in and out,

The wan stars danced between.

And the coming wind did roar more loud,

And the sails did sigh like sedge;

And the rain poured down from one black cloud;

The Moon was at its edge.

The thick black cloud was cleft, and still

The Moon was at its side:

Like waters shot from some high crag,

The lightning fell with never a jag,

A river steep and wide.

The loud wind never reached the ship,

Yet now the ship moved on!

Beneath the lightning and the Moon

The dead men gave a groan.

They groaned, they stirred, they all uprose,

Nor spake, nor moved their eyes;

It had been strange, even in a dream,

To have seen those dead men rise.

The helmsman steered, the ship moved on;

Yet never a breeze up blew;

The mariners all ’gan work the ropes,

Were they were wont to do:

They raised their limbs like lifeless tools-

We were a ghastly crew.

The body of my brother’s son,

Stood by me, knee to knee:

The body and I pulled at one rope,

But he said nought to me.

“I fear thee, ancient Mariner!”

Be calm, thou Wedding–Guest!

’Twas not those souls that fled in pain,

Which to their corses came again,

But a troop of spirits blest:

For when it dawned – they dropped their arms,

And clustered round the mast;

Sweet sounds rose slowly through their mouths,

And from their bodies passed.

Around, around, flew each sweet sound,

Then darted to the Sun;

Slowly the sounds came back again,

Now mixed, now one by one.

Sometimes a–dropping from the sky

I heard the sky–lark sing;

Sometimes all little birds that are,

How they seemed to fill the sea and air

With their sweet jargoning!

And now ’twas like all instruments,

Now like a lonely flute;

And now it is an angel’s song,

That makes the Heavens be mute.

It ceased; yet still the sails made on

A pleasant noise till noon,

A noise like of a hidden brook

In the leafy month of June,

That to the sleeping woods all night

Singeth a quiet tune.

Till noon we quietly sailed on,

Yet never a breeze did breathe:

Slowly and smoothly went the ship,

Moved onward from beneath.

Under the keel nine fathom deep,

From the land of mist and snow,

The spirit slid: and it was he

That made the ship to go.

The sails at noon left off their tune,

And the ship stood still also.

The Sun, right up above the mast,

Had fixed her to the ocean:

But in a minute she ’gan stir,

With a short uneasy motion–

Backwards and forwards half her length

With a short uneasy motion.

Then like a pawing horse let go,

She made a sudden bound:

It flung the blood into my head,

And I fell down in a swound.

How long in that same fit I lay,

I have not to declare;

But ere my living life returned,

I heard and in my soul discerned

Two voices in the air.

“Is it he?” quoth one, “Is this the man?

By him who died on cross,

With his cruel bow he laid full low,

The harmless Albatross.

“The spirit who bideth by himself

In the land of mist and snow,

He loved the bird that loved the man

Who shot him with his bow.”

The other was a softer voice,

As soft as honey-dew:

Quoth he, “The man hath penance done,

And penance more will do.”

BUT tell me, tell me! speak again,

Thy soft response renewing–

What makes that ship drive on so fast?

What is the ocean doing?

Still as a slave before his lord,

The Ocean hath no blast;

His great bright eye most silently

Up to the Moon is cast–

If he may know which way to go;

For she guides him smooth or grim

See, brother, see! how graciously

She looketh down on him.

But why drives on that ship so fast,

Without or wave or wind?

The air is cut away before,

And closes from behind.

Fly, brother, fly! more high, more high

Or we shall be belated:

For slow and slow that ship will go,

When the Mariner’s trance is abated.

I woke, and we were sailing on

As in a gentle weather:

’Twas night, calm night, the Moon was high;

The dead men stood together.

All stood together on the deck,

For a charnel–dungeon fitter:

All fixed on me their stony eyes,

That in the Moon did glitter.

The pang, the curse, with which they died,

Had never passed away:

I could not draw my eyes from theirs,

Nor turn them up to pray.

And now this spell was snapt: once more

I viewed the ocean green.

And looked far forth, yet little saw

Of what had else been seen–

Like one that on a lonesome road

Doth walk in fear and dread,

And having once turned round walks on,

And turns no more his head;

Because he knows, a frightful fiend

Doth close behind him tread.

But soon there breathed a wind on me,

Nor sound nor motion made:

Its path was not upon the sea,

In ripple or in shade.

It raised my hair, it fanned my cheek

Like a meadow–gale of spring–

It mingled strangely with my fears,

Yet it felt like a welcoming.

Swiftly, swiftly flew the ship,

Yet she sailed softly too:

Sweetly, sweetly blew the breeze–

On me alone it blew.

Oh! dream of joy! is this indeed

The light–house top I see?

Is this the hill? is this the kirk?

Is this mine own countree!

We drifted o’er the harbour–bar,

And I with sobs did pray–

O let me be awake, my God!

Or let me sleep alway.

The harbour-bay was clear as glass,

So smoothly it was strewn!

And on the bay the moonlight lay,

And the shadow of the moon.

The rock shone bright, the kirk no less,

That stands above the rock:

The moonlight steeped in silentness

The steady weathercock.

And the bay was white with silent light,

Till rising from the same,

Full many shapes, that shadows were,

In crimson colours came.

A little distance from the prow

Those crimson shadows were:

I turned my eyes upon the deck–

Oh, Christ! what saw I there!

Each corse lay flat, lifeless and flat,

And, by the holy rood!

A man all light, a seraph–man,

On every corse there stood.

This seraph band, each waved his hand:

It was a heavenly sight!

They stood as signals to the land,

Each one a lovely light:

This seraph-band, each waved his hand,

No voice did they impart–

No voice; but oh! the silence sank

Like music on my heart.

But soon I heard the dash of oars;

I heard the Pilot’s cheer;

My head was turned perforce away,

And I saw a boat appear.

The Pilot, and the Pilot’s boy,

I heard them coming fast:

Dear Lord in Heaven! it was a joy

The dead men could not blast.

I saw a third – I heard his voice:

It is the Hermit good!

He singeth loud his godly hymns

That he makes in the wood.

He’ll shrieve my soul, he’ll wash away

The Albatross’s blood.

THIS Hermit good lives in that wood

Which slopes down to the sea.

How loudly his sweet voice he rears!

He loves to talk with marineres

That come from a far countree.

He kneels at morn and noon and eve-

He hath a cushion plump:

It is the moss that wholly hides

The rotted old oak–stump.

The skiff-boat neared: I heard them talk,

“Why this is strange, I trow!

Where are those lights so many and fair,

That signal made but now?”

“Strange, by my faith!” the Hermit said-

“And they answered not our cheer!

The planks looked warped! and see those sails,

How thin they are and sere!

I never saw aught like to them,

Unless perchance it were

“Brown skeletons of leaves that lag

My forest–brook along;

When the ivy–tod is heavy with snow,

And the owlet whoops to the wolf below,

That eats the she–wolf’s young.”

“Dear Lord! it hath a fiendish look-

(The Pilot made reply)

I am a–feared” — “Push on, push on!”

Said the Hermit cheerily.

The boat came closer to the ship,

But I nor spake nor stirred;

The boat came close beneath the ship,

And straight a sound was heard.

Under the water it rumbled on,

Still louder and more dread:

It reached the ship, it split the bay;

The ship went down like lead.

Stunned by that loud and dreadful sound,

Which sky and ocean smote,

Like one that hath been seven days drowned

My body lay afloat;

But swift as dreams, myself I found

Within the Pilot’s boat.

Upon the whirl, where sank the ship,

The boat spun round and round;

And all was still, save that the hill

Was telling of the sound.

I moved my lips – the Pilot shrieked

And fell down in a fit;

The holy Hermit raised his eyes,

And prayed where he did sit.

I took the oars: the Pilot’s boy,

Who now doth crazy go,

Laughed loud and long, and all the while

His eyes went to and fro.

“Ha! ha!” quoth he, “full plain I see,

The Devil knows how to row.”

And now, all in my own countree,

I stood on the firm land!

The Hermit stepped forth from the boat,

And scarcely he could stand.

“O shrieve me, shrieve me, holy man!”

The Hermit crossed his brow.

“Say quick,” quoth he, “I bid thee say–

What manner of man art thou?”

Forthwith this frame of mine was wrenched

With a woeful agony,

Which forced me to begin my tale;

And then it left me free.

Since then, at an uncertain hour,

That agony returns;

And till my ghastly tale is told,

This heart within me burns.

I pass, like night, from land to land;

I have strange power of speech;

That moment that his face I see,

I know the man that must hear me:

To him my tale I teach.

What loud uproar bursts from that door!

The wedding–guests are there:

But in the garden–bower the bride

And bride–maids singing are:

And hark the little vesper bell,

Which biddeth me to prayer!

O Wedding-Guest! this soul hath been

Alone on a wide wide sea:

So lonely ’twas, that God himself

Scarce seemed there to be.

O sweeter than the marriage–feast,

’Tis sweeter far to me,

To walk together to the kirk

With a goodly company!–

To walk together to the kirk,

And all together pray,

While each to his great Father bends,

Old men, and babes, and loving friends,

And youths and maidens gay!

Farewell, farewell! but this I tell

To thee, thou Wedding–Guest!

He prayeth well, who loveth well

Both man and bird and beast.

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things both great and small;

For the dear God who loveth us

He made and loveth all.

The Mariner, whose eye is bright,

Whose beard with age is hoar,

Is gone: and now the Wedding–Guest

Turned from the bridegroom’s door.

He went like one that hath been stunned,

And is of sense forlorn:

A sadder and a wiser man,

He rose the morrow morn.

— Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Thursday, 3 August, 2023; ver2023v1